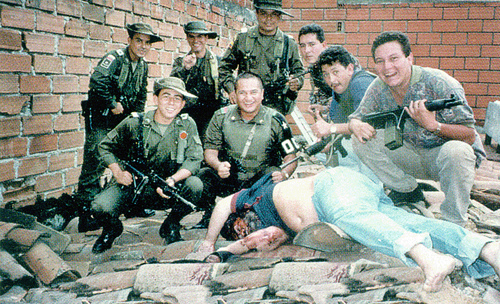

Photo via Andy Zeigert, Flickr.

Medellín boss Pablo Escobar moments after being gunned down in Dec. 1993, after a joint Colombian-U.S. manhunt operation.

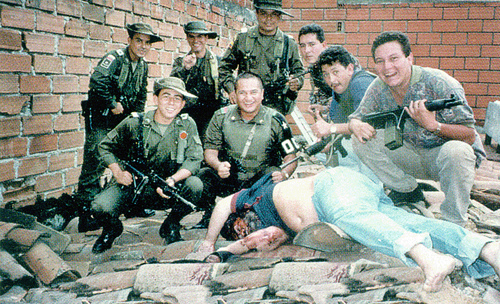

Photo via Andy Zeigert, Flickr.

Medellín boss Pablo Escobar moments after being gunned down in Dec. 1993, after a joint Colombian-U.S. manhunt operation.A telling article featured this past Wednesday in the Washington Post underlines a flux of coca cultivation in the Andean region over the past five years– not that this should come as some inherent revelation to us all. With the United States Government spending nearly $4 billion on drug eradication and interdiction programs during this period and the crop yield flowing rather unabated, the aims of U.S. security initiatives in Latin America can be labeled a bit, shall we dare say, out of touch?

The irony of course is that these five years stretch back to another three decades of almost stagnant policy, littered with short-lived tactical successes and exhausted rhetoric. Indeed, the nature of narcotics trafficking and its actors have morphed over time, however the bottom line for U.S. drug policy has not. It continues to emphasize the destroying of the product rather than addressing the conditions under which its trade flourishes.

Recently, I debated the merits of the multifaceted Plan Colombia, detailing how American efforts in counternarcotics have challenged traditional political paradigms and have been blurred by the lofty aims of several administrations. As I note, there has been a fair measure of success in Colombia via a restoring of state legitimacy and relative sovereignty over major territory. This, however, remains a secondary objective to U.S. eradication efforts in the region.

With drug related violence spilling across greater Mexico and the United States moving to counteract its influence in much the same manner via its Plan Merida, history can offer us some choice wisdom. Here follow ten lessons Uncle Sam can hash from his fabled ‘War on Drugs’:

1. Understand the changing nature of the beast: Narcotics trafficking in Latin America has continually evolved in both organizational structure and operational orientation in recent decades, moving away from hierarchical vulnerabilities toward flexible, “snap-in” nodes. These operate among a viral network of transnational organized crime and fringe political groups now utilizing established routes to North America via Mexico and through western Africa onward to the European theatre.

2. Counternarcotics and counterinsurgency are not mutually exclusive: Illicit actors capitalize on bureaucratic rules of engagement. Seen early on in Plan Colombia, U.S. policy under the Clinton administration held the prerequisite that action taken with its material support, active or implicit, should strictly target narcotics strongholds. This essentially fractured a unified strategy toward combating armed actors that threatened state legitimacy before the Colombian populace. U.S. counternarcotics operations must be conducted within the lens of bolstering domestic state security and fortifying of judicial apparatuses against corruption.

3. The prevalence of narco affairs in Latin America, in part, results from U.S. neglect to engage the region on larger issues: Let’s face it, Latin America has until very recently been the forgotten theatre in U.S. foreign policy endeavors and its national security agenda. Sure, the usually banter of Hugo Chávez and his Bolivarian revolution stir the Washington pot every now and then, but the more illusive reality remains that the tide of illicit commerce and migration found in the region, be it human smuggling, gun-running, or narcotics trafficking, is testament to sparse economic opportunity and rabid corruption of state institutions by powerful mafia actors. Measures by the U.S. to promote transparent governance, state responsibility, and economic incentives for fulfilling such have been sorely lacking to bear much resemblance of Good Neighbor policy.

4. While narcotics trade may not always be politically oriented, fighting it is: Ardent diplomacy and political negotiation among American states remains crucial in combating the transnational threat posed by cartels and sub-state insurgents. Unless a level of cooperation and a unified initiative are adopted to promote inter-state security, subversive organizations will aim to exploit these state quarrels, whether they are politically oriented in orientation or not– it’s in their own self interest to pit the region’s regimes against themselves and the lever of U.S. strategy.

5. Targeting narcos draws strange bedfellows: Aka. “blowback”. As one can readily see in the unfolding parapolitcal scandal on the contemporary Colombian stage, and through much of U.S. cold war policy in the region, crushing insurgencies forges some ugly alliances with vigil ante groups. Remember Los Pepes stalking drug kingpin Pablo Escobar amid U.S. support?…those same leaders subsequently led paramilitary death squads in record disappearances of Colombian campesinos.

6. This is a domestic battle as much as a transnational plague: There is a fundamental reason the narcotics industry draws billions of dollars annually from its sales and arms itself with military grade weapons– yep you guessed it, U.S. supply and demand. Until this issue is addressed from both sides of the aisle, its going to take a lot of Hail Mary‘s and super-duper border walls to combat American demand for blow and ganja.

7. It is a campaign that can never be won, but can be properly managed: No way to kill all the cannabis and coca plants south of the border, even with the magic touch of Round-up. No way to blockade every one of those superfluous routes to the U.S. or Europe, or even to hunt down the industry’s school of big flounders. This is not a war that can be won by numbers or decisive blows, it is a campaign that should aim to manage state authority, exercise territorial control, and provide attractive alternatives to the struggling populace.

8. States should be rewarded for complicity, not shunned and isolated for alternative agendas: U.S. policy of disengagement has not proven to be very fruitful in terms of national security or furthering of inter-American cooperation. Shunning Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador as pariahs for their “alternative” approach to collective nationalism has only worked against efforts at diminishing supply and financing of fringe opposition. While these states work to build opposition to American influence, they dangle carrots to smaller nations prone to sway by incentive (petroleum, mining, natural gas, medical aid, etc.). U.S. apathy imparts a political vacuum in the region.

9. Foreign aid should be distributed based on fulfilled benchmarks: Instead of penalizing and sanctioning American states for not complying directly with U.S. strategy, reward their demonstrated efforts to achieve compromised objectives. Demonizing regimes such as that of Morales, Chávez, and Correa only plays into their domestic cards. Hasn’t the United States had a fair measure of success in other regions of the world following this very same premise?

10. The United States Government is more than capable of leading a regional security initiative and promoting a level of stability to the Americas: The United States with its regional partners has had more than its fair share of known tactical successes against cartels and insurgent groups in Latin America. Look to the training of Colombian special forces in recent years to curtail the FARC, the capture and extradition of major mafiosos, the fall of the Medellín and Cali cartels in the 1990s, the disruption of international cells operating in the southern cone, among thousands of major seizures and raids from actionable intelligence. The problem has never been one of capability or even sheer logistics when cooperation is forged…it has been a matter of political vision and overarching strategy. That shift needs to be made to the larger picture, foregoing the eternal quest to burn the mother of all drug caches, toward the understanding that security interests are served by promoting strong governance of the American states.

Among these few, I’m quite sure there are many more valuable lessons that can be gleaned from the counternarcotic campaigns of Latin America, amid other international bouts of transnational crime. Feel free to weigh in and let us know, what do you see as cornerstone to pan-American security?